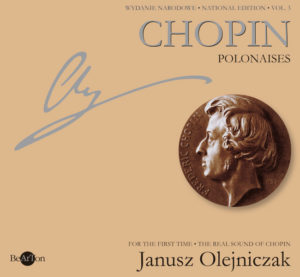

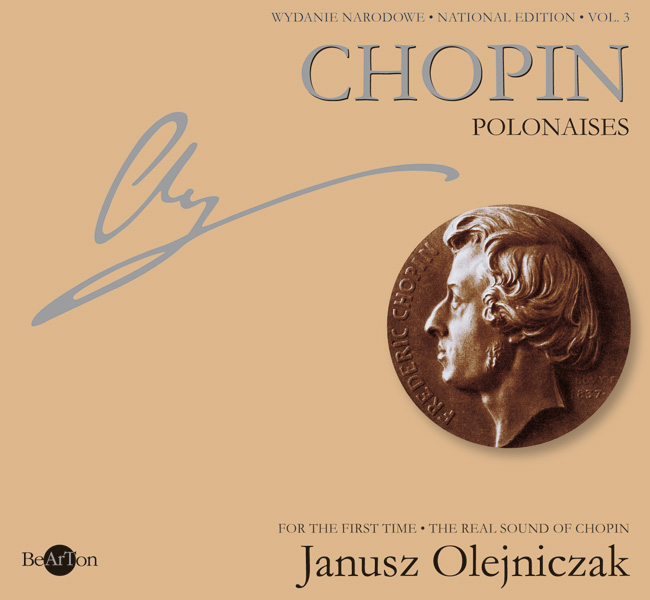

Chopin – Polonaises

Chopin – Polonaises

Cat. No. CDB005

Music disc: CD-AUDIO

Performer:

Janusz Olejniczak – piano

CD content:

- Polonaise op. 26 no. 1 in 1 C sharp minor – 8’54”

- Polonaise op. 26 no. 2 in E flat minor – 8’05”

- Polonaise op. 40 no. 1 in A major – 5’22”

- Polonaise op. 40 no. 2 2 in C minor – 7’50”

- Polonaise op. 44 in F sharp minor – 11’02”

- Polonaise op. 53 in A flat major – 7’02”

- Polonaise-Fantasia op. 61 in A flat major – 13’14”

Total time – 62’09”

Prizes:

Listen a part

42.99złAdd to basket

© ℗ 1997 Bearton

Polonaises

Polonaise comes from the folk dance called: chodzony (processional). On the turn of the 18th century it turned into a popular social dance that added splendour to dinners, feasts, and festivities at manor houses and castles. It was probably when its French reading: polonaise originated. The name Polonaise was used along with another name, i.e. Polish, even when the dance gained the national status as a patriotic symbol. It`s stylised artistic form was refined by Micha! Kleofas Ogiński, whose compositions – performed everywhere – played a crucial role especially after the loss of independence. Ogiński thus initiated a separate musical trend, dominated by the polonaise character. The writing of polonaises was continued by Józef Elsner, Maria Szymanowska, Karol Kurpiński, Jan Stefani, and many other composers of the turn of the 18th century.

That manifold tradition as well as the popularity of stylised piano forms of polonaise influenced the creative imagination of young Chopin. His first juvenile improvisations were based on polonaise rhythm: and his first compositions, written at the age of seven, had the form of polonaise. In fact, his fascination with both polonaise and mazurka (equally important form) is of the basic importance for the whole Chopin output from the very beginning till the end of his life. However, it is not only because polonaises, his first works, and mazurkas, the latest, are the most numerous among his works. This two main types influenced other forms with a kind of thematic material (rondo refrains), peculiar measure and rhythmic (dance ballads and scherzos), as well as a sort of tonality (the influence of mazurkas’ modal scale).

The classical form and traditional content of three early polonaises and six so called Warsaw polonaises will not be discussed here any further. Instead, polonaises recorded on this album will be described. All of them are different, but at the same time they exemplify three important creative concepts. Two polonaises from Op. 26, in C sharp minor No. 1 and in E flat minor No. 2 – initially named melancoliques – somehow complete each other. They combine lyrical elements (especially exposed melody and mode) with dramatic ones (form creating role of dynamics and peculiar usage of pause). Polonaises in A major and in C minor from the Op. 40 present the conception of heroic polonaise that is both victorious and tragic. It is expressed by simple thematic material, clealry delineated texture, and exposed rhythmical element.

Writing to Julian Fontana from Nohant, in 1841, Chopin described Polonaise in F sharp minor, Op. 44 as a kind of polonaise, though it is fantasia more than anything else. He was aware of a new attitude towards form (with mazurka included in the middle of a composition), and an unconventional way of narration.

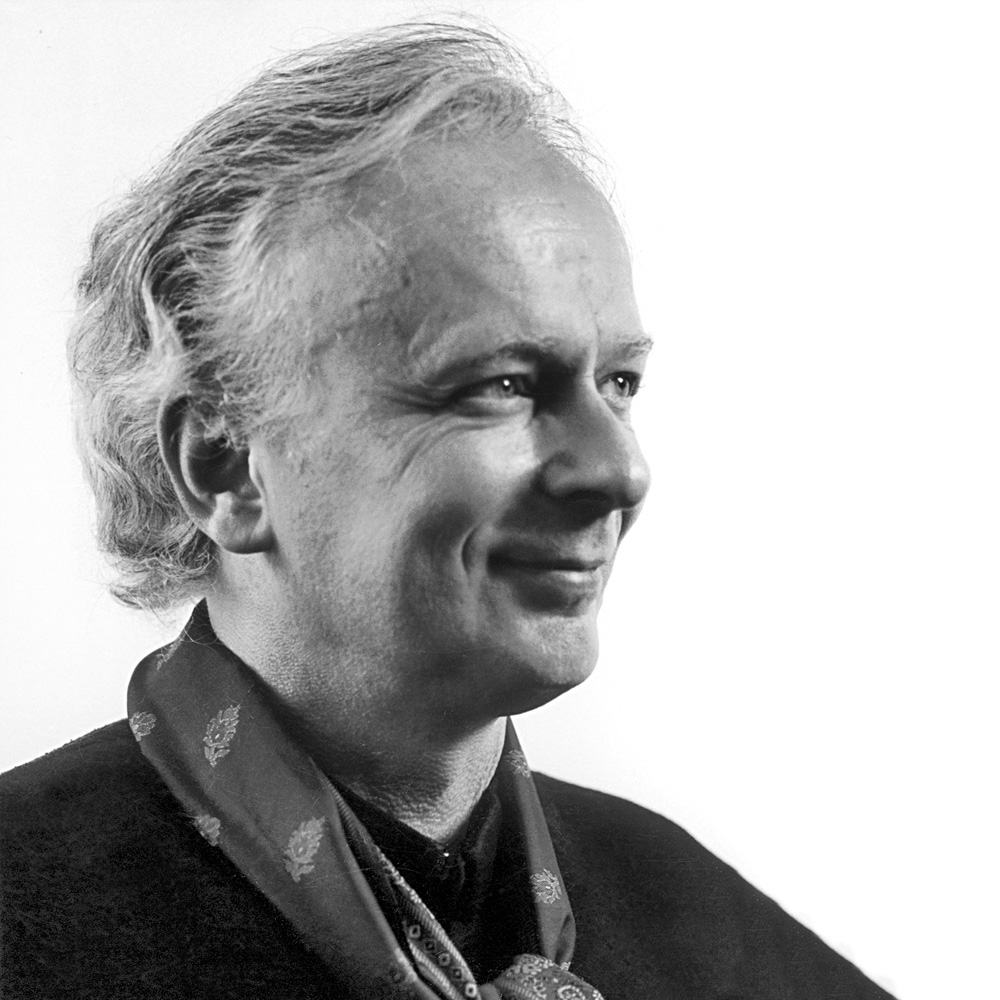

Janusz Olejniczak

This work opens the series of the last three polonaises (except Op. 44, Polonaise in A flat major Op. 53 and Polonaise-Fantasia in A flat major Op. 61) rightly described as dance poems. Preserving the principle of recapitulation, Chopin abandons concise dance form in each of them and introduces elements of rondo and variation, as well as thematic work and polyphony. Therefore, he reaches at free form where individual tonal plans are established by superior rules of expression. Expressive categories of the last polonaises include maestoso, con brio, appasionato, and numerous interpretative specifications that indicate dramatic moments, seriousness, dignity, power, impetus, heroism, as well as elements of ballad epic poetry. Numerous themes along with quasi improvisatory narration result in perception of last polonaises as the series of pictures painted with sound (especially pictures referring to the uprising, and national and liberation symbolics), or subjective, non-restricted visions. However, those dance poems embody – first and foremost – the novel idea of dance apotheosis. According to this idea, stylistic sublimation becomes possible due to the power of dance experienced. The idea of dance apotheosis was subsequently taken over and developed by Neo-romantics and Impressionists.

Marek Wieroński

Translation: Joanna Janecka

Review

Janusz Olejniczak nie bawi się w przesadne romantyzowanie czy sentymentalizowanie, bo i nie czas na to w polonezie, lecz ukazuje Chopina wielkiego, dumnego, z wysoko uniesionym czołem {…}. Nie ulega melancholii, jest konkretny i rzeczowy. Przedstawia polonezy jako wielkie poematy narodowe.

![Chopin – Walce [B] i inne utwory CDB047](https://www.bearton.pl/wp-content/uploads/Chopin-Walce-B-i-inne-utwory-CDB047-A-300x277.jpg)

![Chopin – Pieśni [B] CDB046](https://www.bearton.pl/wp-content/uploads/Chopin-Piesni-CDB046-A-300x277.jpg)

![Chopin - Mazurki i inne utwory [B] CDB038](https://www.bearton.pl/wp-content/uploads/Chopin-Mazurki-i-inne-utwory-B-CDB038-A-300x277.jpg)

![Chopin – Polonezy [B] CDB037](https://www.bearton.pl/wp-content/uploads/Chopin-Polonezy-B-CDB037-A-300x277.jpg)